Steps of the Archive

The tall bell tower of Magister Deusdedit rises from the abbey castle to reassure the silent pilgrim who walks with his staff along the Via Romea through the insula on his long and perilous journey to the Holy Land. Dawn illuminates the Volana piscaria, the mass of Lagosanto, Ostellato and the Baoria fundum, it lights up the port, the woods, the cultivated fields, the woods, the houses, the chapels, the churches, scattered from Ferrara to Romagna, as far as Marche, Umbria, Veneto, Lombardia and Piemonte and strikes the monasterium façade with the colour of terracotta, brick and polychrome vases. Here are the lion, the peacock and the eagle, caressed by the singing of the hundred vibrant voices of the Benedictine matins. Here are the peasants swarming on the boats of the Po and the ringing of the bell to free the numerous familia of monks towards the scriptorium, the tribunal, the armarium of Abbot Girolamo’s books, the herbalist’s shop, the refectory, the kitchens, the factories, the fields. Finally the green of the cloister, the smell of the stone, here is Sancta Maria in Comaclo, qui vocatur in Pomposia, Benedictine fervour, halfway between Cluny and Montecassino. Pomposa is, in the heart of the 1000 year, the Middle Ages: wisdom, faith, music, art, power, imaginative force, beauty, wonder. Guido, inventor of musical notation (modo in Italiam primum), then Mainardo and then Girolamo governed the abbey in the 11th century and built its political, economic, spiritual and cultural greatness.

The bell tower of the Abbey seen from the loggia in front of Palazzo della Ragione

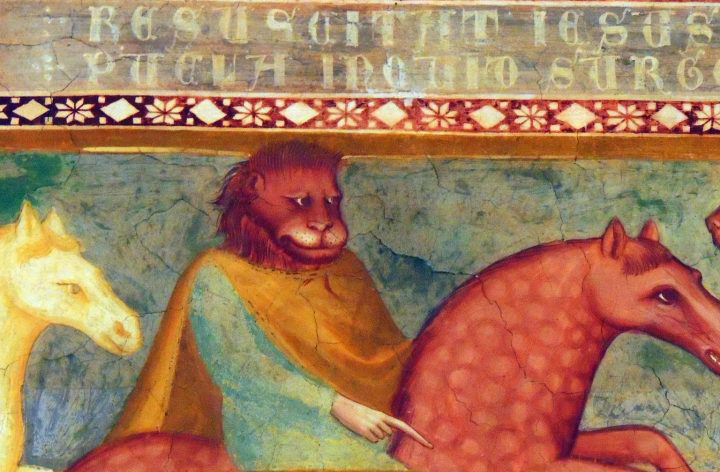

Three centuries later, a descendant of the same pilgrim would have found on his passage the insula, the woods, the cultivated fields, the wealth that came from this environment, in slow and inexorable decline. He would have seen with his own eyes the traces of the slow agony of the Po, the disasters of the catastrophic “routes” and the vast floods. He would also have known of the misgovernment of Abbot Anselm, deposed (1199) by the Pope for “simony, perjury, squandering and insufficiency”, of the squandering of the patrimony of Abbot Alberto (1230-1245) to pay creditors, of the squabbling among the monks during the election of Abbot Giacomo (1286-1292), of the raids by the Ferrarese, destined over time to expropriate the abbey of its territories and rights. Having survived his journey at least up to that point, eating in the refectory and gazing into the chapter house, he would have admired the frescoes in the manner of Giotto and recognised that little magpie, symbol of the authority of Abbot Enrico (1302-1320). And in the evening shadows, on that plain, entering the abbey church, walking, looking up, along the nave to the counter-façade of the apse, he would have felt the same visionary dismay as John: Patmos, the seven candlesticks, the book of the seven seals, the lamb and the evangelists, the cavalcade of the horsemen of the Apocalypse, the four angels, the sixth trumpet, the woman, the dragon, the beasts, Babylon, the Avenger, Satan and the abyss, the second parousia, the Last Judgement, the heavenly Jerusalem. Impressed, he would have thought of a painter and an abbot, of the colours and imagination of Vitale da Bologna and his pupils, who had created that sort of Biblia pauperum from nothing, shaping the words with imagination and colour, and of Andrea di Fano (1336-1361), the last great abbot of Pomposa, a man who survived the black plague, guardian of a precious centuries-old tradition, alone against the decadence of faith, in a monastery now completely devoid of the evocation of that religious fervour that had inflamed for two years the days spent at Pomposa by St Pier Damiani, between study and prayer.

Detail of the wall frescoes (lower band, Apocalypse of St. John)

In the warm spring of 1563, abbot and monks left Pomposa, in the insula only a few tired monks remained on guard. They have lost the memory of the universe from which they came. And with the memory also the archive is lost. Two capse cum cartis et instrumentis diversarum rationum, resounds the voice of ser Francesco Pellipari, while he is reading to the abbot Rainaldo d’Este, the patrimonial inventory that he has commissioned him and that lists the documents, the books, the sacred furnishings of the monastery. This scanty piece of information is the first flag of a long and still unfinished “hunt” for the treasure of the Pomposa Tabularium papers.

It was 1459 and the archive was still in its original location.

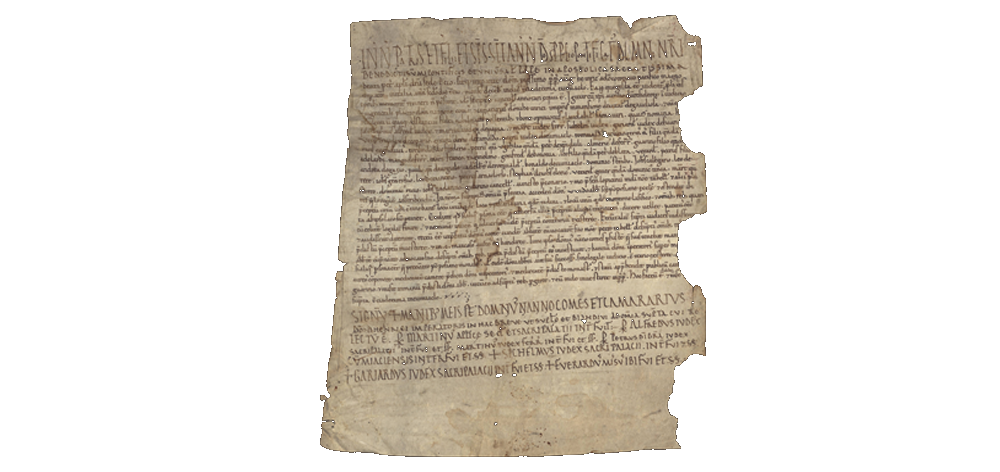

Parchment of the Pomposian Archives

A little more than a century later, in 1563, the archive also travelled with the luggage of the abbot and the monks who left the insula for the monastery of San Benedetto in Ferrara. However, the most important public documents, privileges and imperial and papal diplomas (47 units for the years 1001-1410), which the commendatory abbots of the Este family took from the Tabularium and forfeited to the archives of the Signoria, now in the State Archives of Modena, no longer belong to it. The Este family also “stole” the privilege of Henry IV of Franconia for Pomposa, a document of particular elegance: the emperor of the episode of Canossa, who had as his godfather an outstanding Benedictine, Hugh Abbot of Cluny, had it drawn up by his chancellery in gold ink on purple parchment.

At San Benedetto, the papers were reordered, described and marked by the monk Ludovico Morini. The year is 1674. Tiny tags, of which there are still traces, are attached to each parchment with the indication of the letter of the capsule and the progressive number of the parchment (B89 is the signature “Morini”). His inventory, complete with the registers, is now lost, except for two partial copies, kept in Ferrara and Montecassino, from which it is possible to obtain the registers of 302 documents, up to parchment B89. Perhaps it was in 1720, during a stay in Ferrara, that the historian, scholar and abbot Benedetto Bacchini rearranged, recorded and re-marked the parchments of the Pomposa, dividing them into bundles of thirty and placing them in drawers (B.VI.23, is the signature “Bacchini” that indicates the number 23 of the parchment, the bundle VI to which it belongs, the drawer B in which the bundle is placed).

Bacchini’s chronological index, annotated and integrated by the author himself and then by the Cassinese monk Placido Federici, is preserved in its original form in the Braidense Library in Milan, while a contemporary copy, annotated and integrated like the original, is in the Diocesan Archive of Ferrara. Then it was the turn of the “historian of Pomposa”, Placido Federici, who, under the encouragement of his brother, decided to make his Ferrara exile in San Benedetto easier by compiling a great history of the abbey of Pomposa in three volumes.

To this end, between 1773 and 1778, with the help of the young monks of the monastery, he copied into the eight volumes of the Codex Diplomaticus Pomposianus, now in the Montecassino Archives, two thirds of the parchment documents that were in the Tabularium at that time. All this erudite fury was dramatically interrupted by the French suppression of the religious corporations. The year 1797 marked the turn of San Benedetto in Ferrara.

The papers of Pomposa followed the fate of those of the other suppressed monasteries: few parchments remained in Ferrara, and today they are in the Diocesan Historical Archive in the San Benedetto fund, while most of them, destined to the future “Central Archive of the Kingdom of Italy”, left for Milan towards the great Diplomat of the Kingdom.

Today, only a small part of the Pomposa papers, 194 units, is preserved in the State Archives of Milan, in envelope 20 of the Diocesan Museum Fund and in envelope 713 in the Parchment Fund. But the journey was far from over. In 1808, the director of the Milan Archives reported that in 1817 about 9,000 parchments had been returned to the city of Ferrara and that they had been stolen and lost on the return journey. It is a fact that many Ferrara papers appeared on the antiques market, many being part of the chartes ou diplomes collection of Count Carlo Morbio of Novara. From here and through different channels they reached, in two separate blocks, the State Archive of Rome, which bought them in 1884 and kept them in the Collection of Parchments, Pomposa, boxes 199200 (1002 parchments and 150 manuscripts) and in the private Archive of the Abbey of Montecassino.

In 1882, about 3100 parchments from Ferrara arrived at Montecassino, donated by Frederick of Furstenberg, archbishop of Olmutz (today Olomouc in the Czech Republic), which are today preserved in 105 files. Of these, about 2000 are referred to Pomposa (Fondo Carte di Pomposa) and recorded between 1882 and 1888 by don Placido Mauro, a monk archivist, on the scrolls still bound to the rolls and in the six manuscript volumes of the Codex Pomposianum. Then, in recent times, “new knights did the feat”: Antonio Samaritani, with the Regesta Pomposiae for the documents between 874 and 1199, published in 1963 and Corinna Mezzetti with the critical edition of the documents between 932 and 1050, in 2016. This is the state of the art. This is the new starting point.

– contribution by Anna Fuggi (pen of sagacious impulse) – detail of the fresco photographed by Antonella Garlandi – interior details of the Abbey and cover photographed by Roberto Romagnoli –